By: Mian Wasif Ali

Over a hundred years ago, Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto observed that 80% of Italy’s wealth was held by just 20% of its population — a finding so persistent it eventually became known as the Pareto Principle. Fast forward to today, and that ratio feels eerily familiar — only now, it’s not just Italy. It’s the Global South.

The Global South — once a vague label for postcolonial, non-aligned nations — has become the epicentre of global inequality. Home to 85% of the world’s population, it produces just 39% of global GDP. This isn’t just a gap — it’s a structural abyss. And while technology is leaping forward at breakneck speed in one half of the world, the other half is struggling to light a room.

The Numbers Don’t Lie — But They Don’t Tell the Full Story Either

Inequality isn’t just a moral concern anymore; it’s an economic reality that’s shaping everything from job markets to geopolitics. The Global South’s inequality problem isn’t new — it’s just evolving. While Gini coefficients show us where income gaps are widest (with South Africa leading at a staggering 63%), they don’t show the depth of poverty or the legacy that fuels it.

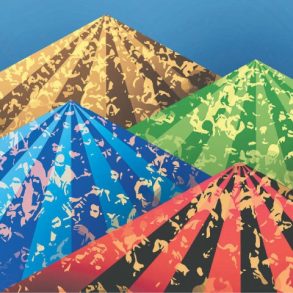

Consider this: nearly 600 million Africans still lack access to electricity. That’s more than 80% of the global electricity access gap. Meanwhile, in the Global North, countries are busy fine-tuning AI models, automating entire industries, and preparing for a future run by algorithms. This contrast — where one part of the world trains machines to think, and the other lights candles to survive — is not just unjust. It’s dangerous.

Inequality Is Engineered, Not Accidental

Much of this imbalance can be traced to colonial legacies that built extractive economies designed to serve a handful of elites. Even post-independence, many nations in the Global South inherited weak institutions, unequal education systems, and tax regimes rigged to protect the wealthy. In some cases, newly empowered local elites simply stepped into the shoes of their colonial predecessors.

Take India, for instance. The so-called “Billionaire Raj” is now more unequal than the British Raj ever was. Since 2000, the top 10% of Indians have expanded their income share from 40% to 58%. The top 1% alone now claim nearly a quarter of all income. Meanwhile, nearly 234 million Indians still live in poverty — more than the populations of many entire countries combined.

This isn’t an Indian anomaly. In Latin America, the richest 10% earn 12 times more than the poorest. In Africa, despite growth, income gains remain heavily skewed. Between 1980 and 2016, the richest 1% of Africans took home 27% of total income growth. Sub-Saharan Africa — with 16% of the world’s population — now shoulders 67% of the world’s extreme poor.

This isn’t just the fallout of failed governance. It’s the result of a global system that rewards capital, not labour. That values profit over people. That automates before it educates.

Enter AI — The New Frontier of Inequality

Technology was once hailed as the great equaliser. But without inclusive policies, it’s becoming the great divider. In advanced economies, automation and AI are accelerating income gaps between the highly educated and everyone else. A study co-authored by Nobel Laureate Daron Acemoglu found that automation alone was responsible for up to 70% of wage inequality growth between 1980 and 2016 in the U.S.

Now, as generative AI goes global, the IMF has warned of even deeper inequality — predicting “winner-takes-all” dynamics as dominant firms monopolise innovation, capital, and data. This wave of automation risks bypassing the Global South entirely, or worse, turning it into a passive consumer of technologies it had no role in shaping.

Pakistan’s Path: Redistribute, Don’t Just Grow

In this grim global context, countries like Pakistan have a choice to make. The country sits atop an estimated $6 trillion in mineral wealth. But without a strategy to ensure equitable distribution, extraction will only reinforce the same structural inequality that has long held it back.

Pakistan’s development model needs a reset — from chasing headline growth to building inclusive prosperity. That means reforming its tax system to make the rich pay their fair share. It means cutting bureaucratic red tape that stifles entrepreneurs while protecting entrenched interests. And it means investing heavily in education, health, and social protection — not just for the few, but for the many.

With nearly two-thirds of the population under 30, Pakistan has a rare demographic window. But youth alone won’t build a future. Education will. Opportunity will. Accountability will.

Social Safety Nets: Not Charity, But Smart Economics

Cash transfers tied to nutrition and schooling. Microloans to women and small entrepreneurs. Subsidies targeted not at the elite, but at the margins where real growth happens. These aren’t idealistic fantasies — they’re proven tools for lifting millions out of poverty. But they require political will, transparent governance, and a break from elite capture.

Equally crucial is depoliticising social welfare. Until programmes are insulated from patronage and deployed with fairness, inequality will remain embedded — not just in income, but in dignity and access.

It’s Time to Redraw the Global Social Contract

The inequality crisis isn’t just a Southern problem. It’s a global one. In the United States, the net worth of its 12 richest billionaires now exceeds $2 trillion — a 193% surge since the early days of Covid-19. The pandemic was a multiplier, not a leveller. It concentrated wealth at the top while pushing millions down the economic ladder.

Unless global leaders — especially those in the North — confront this inequality with urgency, the Pareto Principle will continue to define our era: a shrinking elite hoarding wealth while the majority struggle for crumbs.

The Bottom Line

The Global South isn’t just poor — it’s structurally excluded. From colonialism to AI, inequality has adapted to every era. It’s not accidental. It’s engineered. And it will persist — unless development is redefined.

For Pakistan, and for much of the Global South, the challenge is clear: real development cannot be measured by GDP alone. It must be judged by how evenly prosperity is shared. Until then, the bright lights of innovation will continue to shine in some corners of the world — while the rest are left in the dark.

Want to discuss or republish this article? Reach out to the author or follow for more reflections on inequality, development, and global justice.